Following the global financial crisis, the effectiveness of leadership teams has come under more scrutiny than ever before.

That scrutiny has largely centred on corporate governance, fraud, inappropriate business strategies, or other team dysfunctions such as inattention to results or the avoidance of accountability.

Of course, corporate governance is critical, with boards and executive leadership teams the prime gatekeepers. Yet the dynamics of those teams is almost never explored – mainly because it is not easy to gain access and their proceedings are highly confidential.

Earlier this year, I embarked on a research project, driven by my interest in understanding the reasons behind business failures. I wanted to explore the unconscious processes that come into play when members of leadership teams decide who they are going to trust and why.

During my research, I came across an abundance of evidence that shows how trust occurs between team members, and the role of the hormone oxytocin in building trust.

Those studies, however, focused on administering and measuring the effects of intranasal synthetic oxytocin on individuals or groups.

Structural Dynamics

My own research objective was to measure the existing oxytocin levels of a real-life leadership team, treat that team with an organisational development intervention using

Structural Dynamics, and then measure their oxytocin levels again.

The patterns of human attachment are formed and influenced during the recurrent relationship that a child experiences with their primary caregiver. Oxytocin is the hormone that has been associated with this specific bonding.

Its name comes from Greek words oxús, meaning swift, and tókos, meaning birth. There is a correlation between trust and oxytocin, and there are several studies that have shown evidence to this effect.

The release of oxytocin in the brain during trusting interactions makes humans treat each other as though they are part of the same tribe or family.

Structural Dynamics, devised by US systems psychologist Dr David Kantor, is a model that shows how face-to-face communication may be facilitated or hindered among team members, including the leader.

By making the invisible structure of discourse visible, it uncovers problems in face-to-face communication and helps to bring about change once all unspoken issues are dealt with.

It includes a self-reported psychometric instrument, the results of which provide an individual report, as well as an aggregate team report. In addition to having their oxytocin levels measured, the research participants completed a paper-and-pencil questionnaire on trust before and after the intervention.

I then compared these results with the oxytocin results. A key purpose of the study was to apply an interdisciplinary approach – in other words, to merge knowledge from leadership literature and practice with knowledge from psychology and neuroscience.

Research methodology

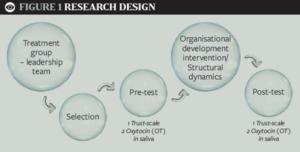

A leadership team from a retail organisation participated in my research. This leadership team consisted of seven members, including the managing director. The research was a quasi-experiment, which took place in a hotel over two days – see Figure 1, below:

A microbiologist measured the oxytocin levels of participants using a saliva swab twice – once at the beginning of day one and again at the end of day two. The participants also completed the paper-and-pencil questionnaire on trust twice, once at the beginning and once at the end of the two days.

Over the course of the two-day experiment, I used Structural Dynamics to explore what trust meant to the participants. There were quite a few misunderstandings regarding the leader’s behaviour towards certain team members, and issues among pairs within the team.

So it was very important to understand where those issues stemmed from, as well as to

distinguish between the impact and intention of a specific behaviour, and to talk openly about participants’ assumptions and expectations with respect to one another.

Results

At the end of the experiment, all participants showed an improvement in the trust scale scores (paper-and-pencil psychometric) once the Structural Dynamics had taken place. The exception was the leader, whose scores remained the same. Interestingly, women’s scores improved more than men’s.

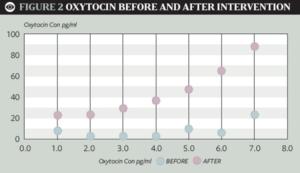

In terms of oxytocin, the oxytocin levels of all participants – including the leader – rose dramatically. See Figure 2, below:

So why did the leader’s score stay the same with the paper-and-pencil questionnaire, but improve dramatically in the oxytocin test? The answer to that question is this: in the paper-and-pencil questionnaire, the leader replied consciously because he believed that having chosen his team, he already had a high level of trust in them.

But his oxytocin levels revealed that his trust in his team actively increased as a result of the Structural Dynamics, despite what he may have wanted to believe. Over the two days, the team members had an opportunity to raise concerns around behaviours and trust.

The discussion was not easy, and the heat and stakes rose, which was a necessary aspect of the intervention. Yet it also led into a ‘disequilibrium’ of the system, which allowed the team members to move forward, resolve misconceptions and arrive at a space where they were able to have these difficult, yet necessary and productive, conversations.

Higher oxytocin levels were therefore evidence of their improved trust. At the end of the two days, the participants came up with an action plan on how to continue to work on team effectiveness, as well as how to cascade the value of trust down their organisation.

Conclusion

From a leadership or management perspective, the implications of being able to build trust are great. Trust creates conscious opportunities for constructive social interaction among team members, or between a leader and team members.

It is crucial to communication, giving and receiving feedback, and establishing a safe environment during a team-building activity.

Thanks to functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans, we can see the impact of our behaviour on someone’s brain. If providing unsolicited feedback to your direct report has the same impact on them as hearing footsteps following them in the dark, imagine what effect you are having on them!

That’s why we need to get to know our biology better and understand that trust is not some near-magical elixir. It is something we can feasibly work towards – and even measure.

Dr Maria Katsarou is managing director of the Leadership Psychology Institute. Contact her by email here and via her blog here

For further thoughts on building trust, check out these learning resources from the Institute

This article was taken from the Yule 2017 edition of Edge magazine

Edge is the quarterly magazine exclusive to members of the Institute. To become a member and receive your copy, click here