Two of China’s top tech titans have extolled the virtues of hard graft with little room for personal or family time.

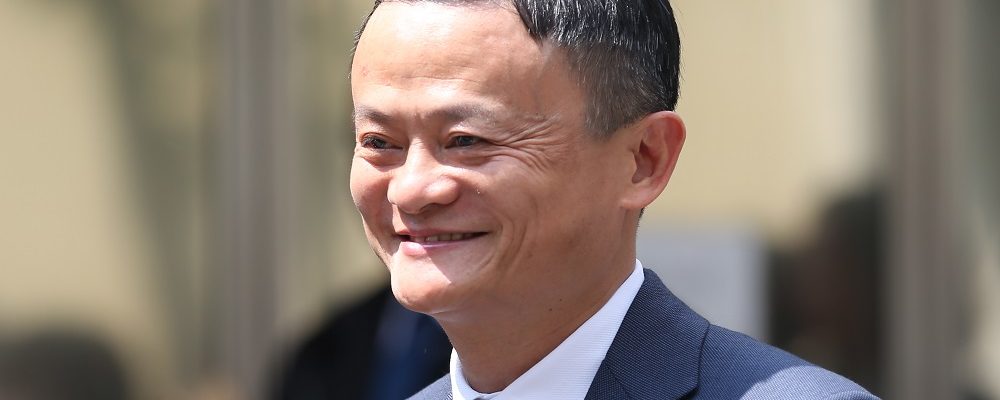

In a speech at the head office of his Alibaba empire on Thursday 11 April, Jack Ma – China’s richest man – talked up his so-called ‘996’ ethos: a rigorous regime in which employees work from 9am to 9pm, six days a week.

While Ma said that he would never actively force anyone to work those hours, he made it clear that he considers them critical to success. According to various reports (see references [1] [2] and [3] below), Ma told his staff: “I personally think that being able to work 996 is a huge blessing. Many companies and many people don’t have the opportunity to work 996. If you don’t work 996 when you are young, when can you ever work 996? If you haven’t done 996 in your life, should you feel proud?”

He added: “In this world, everyone wants success, wants a nice life, wants to be respected. Let me ask everyone: if you don’t put out more time and energy than others, how can you achieve the success you want? If you want to join Alibaba, you need to be prepared to work 12 hours a day, otherwise why even bother joining?”

On the same day, Ma’s rival Richard Liu – founder of JD.com – issued a WeChat post saying: “In the last four, five years [our] number of staff has expanded rapidly. The number of people giving orders has grown and grown, while those who are working have fallen.” As a result, he thundered, “the number of slackers has rapidly grown! If this carries on, JD will have no hope! And the company will only be heartlessly kicked out of the market! Slackers are not my brothers!”

The leaders’ statements sparked heated debate on Chinese social media about what bosses should expect of their staff. But on 14 April, Ma doubled down on his stance. “As I expected,” he wrote in a blog, “my comments internally a few days ago about the 996 schedule caused a debate and non-stop criticism. I understand these people, and I could have said something that was ‘correct.’ But we don’t lack people saying ‘correct’ things in the world today. What we lack is truthful words that make people think.”

He added: “Those who can stick to a 996 schedule are those who have found their passion beyond monetary gains. If you find a job you like, the 996 problem does not exist. [But] if you’re not passionate about it, every minute of work is a torment.”

Is Ma’s stance a frank and honest assessment of what happens when people find jobs they love? Or is it altogether dangerous to proselytise for this approach to working hours?

The Institute of Leadership & Management head of research, policy and standards Kate Cooper says: “Individuals tend to determine for themselves what constitutes work-life balance. If you take a ‘zero-sum’ approach to hours in the day, then you compartmentalise them – you allocate them to work, friends and family, leisure pursuits and so on, and they all balance each other out. But if you take the view that doing the things you love is energising, then your desire to introduce elements of balance will be quashed by the sheer adrenalin you derive from a job that sweeps you away in a fashion that the majority of people only experience from entertainment.”

She notes: “One key issue with the Jack Ma and Alibaba ethos is that of reward. If you’re in a job you love, and you’re really enjoying it, and you’re in the group of people that finds that whole experience energising – and you’re still finding time to eat, sleep and exercise – then who is any one of us to say you shouldn’t be doing that? But if employers are expecting those levels of commitment, and they’re not ensuring that the reward is commensurate or that the work is energising then, in my opinion, their demands are entirely unreasonable.”

Cooper points out: “One of our blogs last year looked at how the TUC is pushing for a shorter working week, on the basis that in increasingly automated economies, working hours ought to reduce. But that may not ring true for every worker in every profession. Indeed, business philosopher and Institute companion Charles Hampden-Turner would cite the Protestant work ethic as key to the success of the British arm of the Industrial Revolution: the rise of mechanisation was underpinned by significant human effort.”

She adds: “There has to be a strong element in this equation of individual choice. As Ma and Liu are effectively conveying, ‘If you can’t stand the heat, stay out of the kitchen.’ But any market in which there is no shortage of jobs will find a level. Organisations simply won’t be able to retain talented staff if they’re not treating them well.”

For further insights on the themes raised in this blog, check out the Institute’s resources on time management

Image of Jack Ma courtesy of feelphoto, via Shutterstock

Like what you've read? Membership gives you more. Become a member.